openUC2 In-line holography

Workshop Manual: Building an Inline Holographic Microscope with UC2

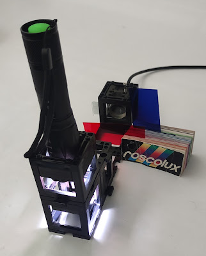

Welcome to our workshop on building an inline holographic microscope using the UC2 modular microscope toolbox. In this experiment, we will create a lensless microscope that demonstrates temporal and coherence properties. By following the steps below, you will construct a simple yet effective holographic microscope to observe transparent samples.

This experiment is an introduction into the UC2 toolbox and should give you a chance to get familiar with the core-idea of creating simple, but also complex optical setups using the modular system.

Here you are going to learn:

- assemble the cube

- add inserts

- arrange multiple cubes

- lensless imaging

This is what you want to build now:

Resources

- OLD an earlier (2019) workshop on this matter can be found here

- CAD the full assembly including the description can be found in the Assembly-folder

- SLIDES for the introduction into holography can be found in the PRESENTATION-folder

Overview

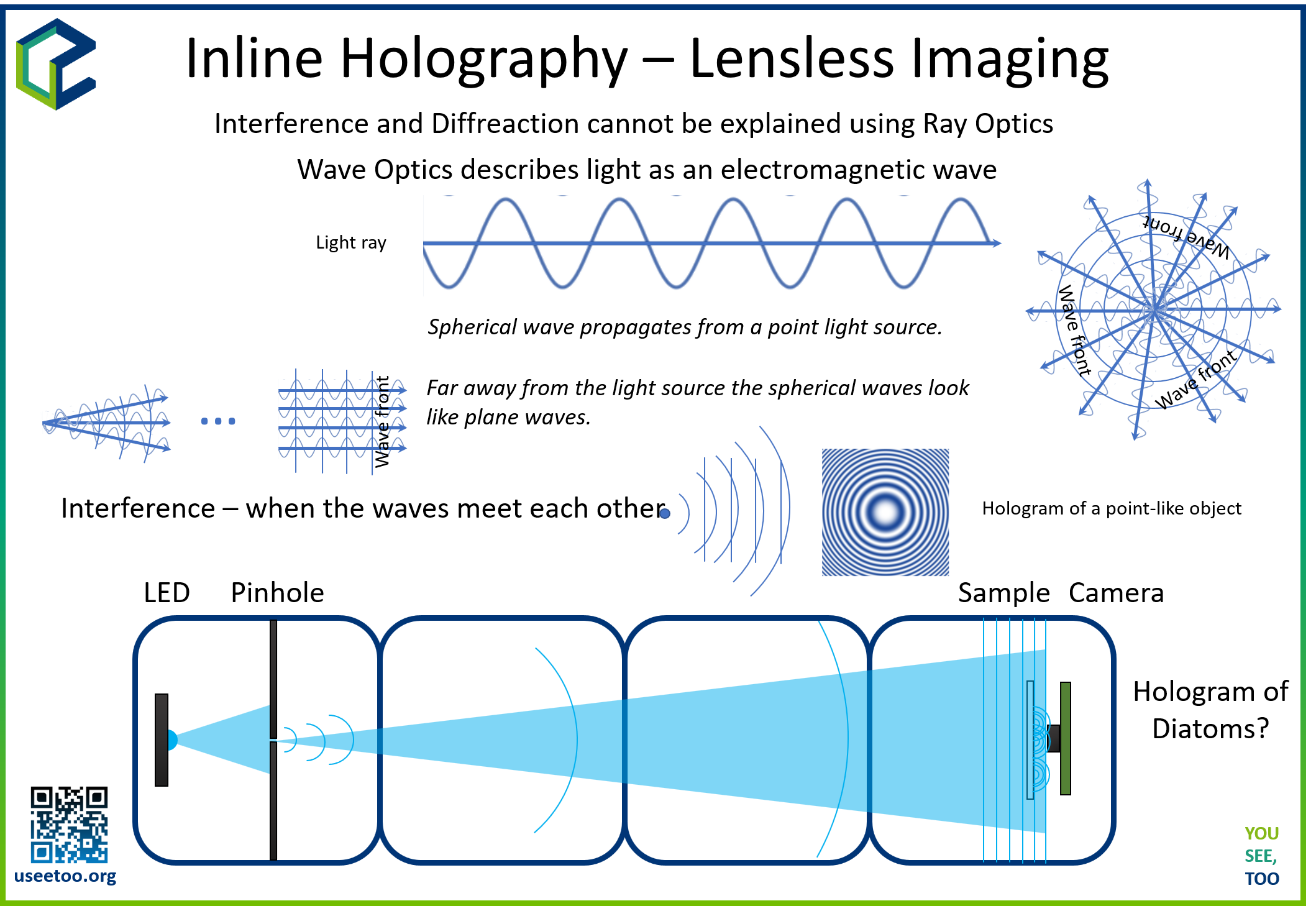

The inline holographic microscope utilizes the principles of holography and coherent light sources to capture and reconstruct 3D images of transparent samples. Instead of using traditional lenses, we rely on interference patterns between a reference beam and the scattered light from the sample. The resulting hologram is then computationally reconstructed to visualize the sample.

Materials Needed

- UC2 Modular Microscope Toolbox (includes cubes and puzzle pieces).

- LED Holder.

- Gel Color Filter.

- Aluminum Foil with a pinhole.

- Transparent Sample (e.g., biological specimen or microstructure).

- Camera Sensor (e.g., ESP32 camera module).

Theory of Operation

Creating the Light Source The holographic microscope begins with a specially prepared light source. An LED, filtered through a gel color filter and focused through a pinhole in aluminum foil, generates quasi-monochromatic coherent light. This coherent light source is essential for the interference patterns necessary for holography.

Sample and Camera Setup A transparent sample is placed in the path of the coherent light source. As the light passes through the sample, it becomes scattered, creating a complex wavefront. The camera, integrated into the same cube as the sample holder, captures this scattered light as an interference pattern, known as the hologram.

Fresnel Propagation When the scattered light reaches the camera sensor, it captures the intensity of the interference pattern. In inline holography, both the object and reference beams travel along the same path to the sensor, causing them to interfere. The Fresnel propagation is used to numerically propagate the hologram from the sensor plane to the object plane and vice versa.

Fresnel propagation is a mathematical process that simulates the propagation of light waves between two planes. It utilizes the Fresnel-Kirchhoff diffraction integral to calculate the complex wavefront at a given distance from the hologram plane. This numerical transformation involves the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), which efficiently converts the hologram from spatial to frequency coordinates.

Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) The FFT is a powerful algorithm used to compute the discrete Fourier transform of an image. It efficiently calculates the frequency components present in an image, providing valuable information about its structure. In our holographic microscope, the FFT is used to transform the captured hologram from real space to frequency space.

The transformed hologram in frequency space contains complex information about the sample's phase and amplitude. However, due to the lensless nature of the microscope, the phase information is lost during the hologram capture process. As a result, additional artifacts, such as the twin-image and ringing artifacts, can occur during hologram reconstruction.

Assembly Steps

Creating the Light Source

- Attach the LED holder to one side of a cube using the provided puzzle pieces.

- Insert the LED into the holder and connect it to an appropriate power source or use the battery-driven one without external power.

- Produce a pinhole using aluminium foil: Take a needle, fold the aluminium foil 8 times, punch a hole, unfold the foil and take the smallest hole that is still intact

- Position the aluminum foil with a pinhole in front of the LED-light source, allowing the light to pass through the pinhole

- Place the gel color filter in front of the aluminium foil to create a quasi-monochromatic coherent light source. .

Setting Up the Sample and Camera

- Place an empty cube right next to the light source cube.

- Position another empty cube on the other side of the light source cube.

- Combine the transparent sample mount and the camera module into a single cube. Mount the sample onto the camera sensor surface, ensuring that there is little space between them.

Assembling the Microscope

- Arrange the cubes in the following order (from left to right): Light Source Cube, Empty Cube, Empty Cube, Sample & Camera Cube.

- Securely mount each cube on puzzle pieces at the lower end and upper bar using the puzzle pieces to ensure stability.

Powering Up the Microscope

- Use the ESP32 camera inside the cube and flash the XIAO firmware

- The link comes here: https://matchboxscope.github.io/firmware/FLASH.html

- Turn on the camera and connect to it via Wi-Fi (the Wifi SSID is Matchboxscope-****, where the number is displayed during boot-up phase in the serial monitor after the flashing process) using a web app or browser (http://192.168.4.1)

- Power on the LED light source.

Adjusting the Contrast

- Check the camera's output for the captured image.

- If the contrast is low due to scattering background light, cover the system with a box or use some shading to prevent direct light from hitting the sensor.

Reconstructing the Hologram

- Capture an image using the ESP32 camera and download it onto your computer (full resolution, i.e. 1600x1200, the capture button in the GUI will offer to download the image, give it some name and save it).

- Start the Jupiter notebook server in the command line.

- (Installation:

pip install jupyterlaband then start it usingjupyterlab) - Create a new Jupiter notebook for hologram reconstruction (see step 7)

- Input the path to the downloaded image file in the notebook.

- Reconstruct the hologram using a fast Fourier transform (FFT) and numerical back-propagation.

- Be aware of twin-image artifacts and potential ringing artifacts in the reconstruction due to interference.

Create a Jupyter notebook and reconstruct the images

The following code will help you go through the process. Create a new Jupyter Notebook, change the path to the file and try it out.

# Import necessary libraries

from io import BytesIO

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

# Define a function to reconstruct inline hologram

def reconstruct_inline_hologram(hologram, wavelength, ps, distance):

# Inverse space

Nx = hologram.shape[1] # Number of columns in the hologram

Ny = hologram.shape[0] # Number of rows in the hologram

fx = np.linspace(-(Nx-1)/2*(1/(Nx*ps)), (Nx-1)/2*(1/(ps*Nx)), Nx)

fy = np.linspace(-(Ny-1)/2*(1/(ps*Ny)), (Ny-1)/2*(1/(ps*Ny)), Ny)

Fx, Fy = np.meshgrid(fx, fy)

# Calculate the kernel using the wavelength and distance

kernel = np.exp(1j * (2 * np.pi / wavelength) * distance) * np.exp(1j * np.pi * wavelength * distance * (Fx**2 + Fy**2))

# Compute the centered FFT of the hologram

E0fft = np.fft.fftshift(np.fft.fft2(hologram))

# Multiply the spectrum with the Fresnel phase factor

G = kernel * E0fft

Ef = np.fft.ifft2(np.fft.ifftshift(G))

# Return the absolute value of the reconstructed hologram

return np.abs(Ef)

# Define an asynchronous function to process the image and reconstruct the hologram

async def process(img, distance=0.007, wavelength=450e-9, pixelsize=5e-6):

img = np.array(img)

holo = reconstruct_inline_hologram(img, wavelength=wavelength, ps=pixelsize, distance=distance)

return holo

# Main function that can be used to continuously process images (currently empty loop)

def main():

while True:

# Properly call the process function with required parameters

pass # Here, you should include the logic to process the images as required

# Read an image

img = plt.imread("/PATH/TO/IMAGE/image.png")

# Process the red channel (index 2) of the image to reconstruct the hologram

holo = await process(img[:,:,2])

# Display the reconstructed hologram

plt.imshow(np.abs(holo))

Assembly Video

In this video you will learn how to setup a UC2 system and also how to build the holographic Microscope

Conclusion

Congratulations! You have successfully built an inline holographic microscope using the UC2 modular microscope toolbox. This simple yet powerful setup allows you to observe transparent samples and explore the fascinating world of holography and coherent light sources. By understanding the principles of Fresnel propagation and Fast Fourier Transform, you can reconstruct digital holograms and visualize 3D structures in your samples. Have fun experimenting with different samples and refining your holographic imaging techniques!

Known Problems

- distance between sensor/sample

- stray Light

- sample not sparse enough

Very Experimental: Reconstruct Holograms with ImSwitch

Prerequirements Here you will finde a guide how to setup the ImSwitch Software:

- Download the Software package from Dropbox

- Install Anaconda (Important: When you're asked to add Anaconda to the

PATHenvironment, sayYES!) - Install Arduino + all drivers

- Install the CH340 driver

- Extract

ImSwitch.zipto/User/$USER$/Documents/ImSwitch(clone or download from GitHub) - Extract

ImSwitchConfig.zipto/User/$USER$/Documents/ImSwitchConfig(clone or download from GitHub) - Optional: Install Visual Studio Code + the Python plugin => setup the Visual studio code IDE for Python

Install ImSwitch for UC2

- Open the anaconda command (Windows + R => "CMD" => enter)

- Type:

conda create -n imswitch - Wait until environment is created

- Type:

conda activate imswitch - Type:

cd /User/$USER$/Documents/ImSwitch - Type:

pip intall -r requirements.txt - Type:

pip intall -e ./ - Type:

imswitch

Reconstruction

This video will show you how to reconstruct holographic data using UC2 and ImSwitch.

Things to explore:

- Get Familiar with ImSwitch

- Get a sparse sample e.g. plankton on coverslip would be best, or just dust/sand/cheeck cells and try to acquire some holograms

Refocusing using ImSwitch

Using the In-line Holography plug-in widget in ImSwitch we can refocus the sample by using a propagator in reverse from the recorded hologram in real-time.

The In-line holography experiment can also be produced with a laser source. In this version of the In-line holography setup, we use white light as source and we use filters to have quasi-monochromatic light illuminating the sample.

ADDITIONAL Speach-to-text

The first experiment will be the inline holographic microscope. This is a relatively simple experiment where we can show both the temporal and especially coherence. We will create a lensless microscope where we use an LED that is filtered by a color filter and pinhole to create a quasi one of chromatic coherent light source. This is then illuminating the transparent sample that is sparse before the scattered wave is sitting the camera sensor. This is relatively simple to build with the C2 system; for this, we only need the LED holder, a gel color filter, as it sees from theaters, aluminum foil where we'll stitch in a hole in order to create a local pinhole, some space between this created light source and the sample, and then the sample that this ultimately glued onto the sensor very closely so that the pinhole virtually scales in size as the ratio between the distance of the light source to the sample and sample to the sensor. In order to build the system, we will place the here created light source on the far left; then another empty cube follows right next to it; then another empty cube follows on the right-hand side; and then we combine the sample mount and the camera into one cube so that the distance between the sample and the camera is minimized. All these cubes should be mounted on puzzle pieces on the lower end and the upper bar so that the whole system becomes stable. We will turn on the camera and also turn on the lights source. Then we go to the web app after connecting to the camera through Wi-Fi, and then we will try to see any variation in the contrast of the camera. If the contrast is not high enough because of this scattering background light, we have to cover the system with a box or with some closing so that there's no straight lights hitting the sensor. This will make a very bad result in the reconstruction. When you're lucky, you can see the sample as a kind of shadow on the sensor already. The core idea now is to reconstruct this digital hologram, where we have to carefully maximize the quality of the file image. Compression artifacts from the ESP32 camera are unavoidable and will eventually degrade the final image results. What we are going to do now is to temper in image and then back propagate the distance from the sensor to the sandal plane using a numerical transformation. What this really means is that we take the image and take every pixel and back propagated by a certain distance numerically. This is done using a fast-year transform where we first fiatransform the image so that it is in frequency space; then we multiply it with a parabolic face Factor, and then we inverse full-year transform the results to end up in real space again. This becomes a convolution of the Fresnel colonel, which essentially propagates every pixel edge of certain distance depending on the wavelength and sampling rate. We can conveniently do that in Python with the Script that is provided by the Jupiter notebook. For this, we go to the website of the ESP32, hit the capture button, and download the image onto the computer. Then we start the Jupiter notebook server by opening the command line in Windows or in Linux and enter Jupiter notebook. Then we go to the browser and open the example Jupiter notebook that will reconstruct our hologram. We will enter the path of our downloaded image file and then reconstruct the results. There are several problems which we can describe but not solve at the moment for stop inland holography, as the name already says, has the problem that the light source and the scattered wave interfere in line. That means the point source will create spherical waves that are propagating its free space and will become almost a plain wave when it's the sample. Here some parts of the wave are scattered where which means that a plane wave is altered in its face depending on the face of the microscopic example, and some portion of the wave is an altered. That means after the sample the unchecked and scattered wave are propagating to the sensor where the two amplitudes are superposing. That means they add up for stuff since our camera detector cannot record amplitudes since the object of frequency is very very high. We are averaging out over time. That means that we will record intensity values in the end. This also means that the information about the face is getting lost. When we are reconstructing the hologram, the color will differentiate whether the sample is before or behind the sensor since the face information is that anymore. This means that in the reconstruction, the so-called twin image always overlays the real image in the end. This causes an avoidable ringing artifacts in the reconstruction. There are some ways to remove it, for example by estimating the face using iterative algorithms or model-based approaches, where we take the full image acquisition process into account. Alternatively, suit also be machine learning algorithms where an algorithm estimates the background and remove these artifacts. However, here we won't use these algorithms as we just want to learn how we can reconstruct the simple.

Some notes on the transform that we have just used here. Briefly, it is a transformation from spatial to frequency coordinates. This sounds very abstract, but for example, our ear does this all the time. When we talk, our voice generates a vibration of the air. That means different frequencies are oscillating and add up to something like noise. Our ear, in turn, has the cochlear where many nerve cells, in turn, are oscillating depending on the resonance frequency of every cell. In a way, they are unmixing the noise and modulate the different frequencies. That means that if you're singing like an A, there is the fundamental frequency and several higher and lower harmonics. And lens does something very similar but in two dimensions. You can have optical frequencies where, for example, a grating that is having stripes that represent on and off and on and off

at a certain distance represent periodic structure. It lens when you place something in the focal plane will then flea transform this into the demodulated frequency components. When you, for example, have a periodic structure like a grating, it will produce two pieces in its Fourier transform or in its focal length on the object side. A fast Fourier transform is its equivalent in the computational science. You can take an image and then represent it in its frequency components for stock that means it tries to estimate the sum of all the different frequency components that make up the image. We use this fast Fourier transform in our code to bring it from real space to frequency space and back again. But since we start with an image without an amplitude or without the face, lack the information.

This property creates additional artifacts since relax the information of the face when we record intensity values on our camera, we also limited to samples that I see like just for the tomt capture in the watcher. The optical resolution of our microscope is bound to the pixel size and the opening angle or the numerical aperture that is created by the illumination and the sensor size that we use to detect the image. However, it is a very nice way of demonstrating how long profil works and how we can detect images without a lens. For stop many different have used it, for example, to detect Malaria in blood. New sins the field of view is very Deutsch.